Writing Wayfire plugins (Part 2)

Hello everyone, this is the next blog in the series about writing Wayfire plugins. Again, I will be writing a custom plugin and explaining the steps along the way. This time however the focus will be on the rendering parts of Wayfire.

Prerequisites

I assume that you are familiar with OpenGL concepts like shaders, programs, textures and framebuffers. If you are not, then you should definitely read up on OpenGL (ES) before continuing, there are many good tutorials on the internet.

Let’s begin!

Let’s assume I am participating in a lets-show-off-my-compositor contest. To get that coveted first place, I want to have rounded corners on all of my applications, so I will be writing a plugin for that.

The plugin should roughly do this:

- Take the window as a GL texture

- Cut off any client-side shadows (for example shadows drawn by GTK). These shadows would otherwise interfere with corner rounding.

- Round off the corners and render to the screen.

There are also a few more implicit requirements. We don’t want our plugin to interfere with other effects in Wayfire like wobbly, fire or blur. We don’t want to round off the background or the panel. We want this effect to work in all modes of operation, for example with scale, expo and cube.

Wayfire’s rendering model

Wayfire’s rendering needs to be efficient and flexible, which necessitates a lot of abstractions, the most important ones being workspace streams and view transformers.

Workspace streams are textures of the views on a given workspace, which is updated on each new frame. They are backed by a wf::framebuffer_t which is an abstraction over plain GL framebuffers.

A transformer is similar to a mathematical function, it takes the texture of the view (the Wayland term for a window) and renders this texture, transforming it along the way. Various transformers can be easily composited together - the first transformer renders to an offscreen framebuffer which is the input of the second transformer. This is the mechanism which lets Wayfire animate a rotated window while blurring it.

What does the code look like?

I hope by now it has become clear that a view transformer can do exactly what we need to round off corners. First, we need a class which implements theh view_transformer_t interface:

#include <wayfire/view-transform.hpp>

class rounded_corners_transformer_t : public wf::view_transformer_t

{

public:

uint32_t get_z_order() override

{

return wf::TRANSFORMER_2D - 1;

}

// ...

};

The get_z_order() method indicates the position of the transformer relative to other transformers. Here, we want to round off corners before any other effects like wobbly, so we request the lowest possible Z order.

wf::region_t transform_opaque_region(

wf::geometry_t box, wf::region_t region) override

{

(void)box;

(void)region;

return {};

}

The opaque region of a view is used for optimizing away redraws behind it. Here we aren’t that concerned with performance so we indicate an empty opaque region (if we did care about performance, we could calculate the regions that are cut off for rounding, subtract them from the given region and return the new region).

wf::pointf_t transform_point(

wf::geometry_t view, wf::pointf_t point) override

{

(void)view;

return point;

}

wf::pointf_t untransform_point(

wf::geometry_t view, wf::pointf_t point) override

{

(void)view;

return point;

}

These two functions take care of transforming pointer, touch and tablet input. transform_point() takes the point in untransformed coordinates (i.e as if the transformer was not there) and returns the coordinates after the transformer is applied. For example: if we have the point (0, 0), the view is centered around (100, 100) and our transformer rotates by 180 degrees, we should return (200, 200).

untransform_point() is the reverse operation.

Our transformer does not rotate, skew or otherwise modify the view, so we don’t need anything special. For 100% accuracy, some parts of the view are actually cut off when rounding, so we should detect whether the input point is inside these regions and return NaN, but in practice this is not a big deal.

wf::geometry_t get_bounding_box(wf::geometry_t bbox, wlr_box region) override

{

(void)bbox;

return wf::geometry_intersection(this->view->get_wm_geometry(), region);

}

This is where things get more interesting. get_bounding_box() returns the bounding box of the given rectangular region after the transformation. Luckily, the calculation is simple - we cut off the part of the window outside of its wm_geometry (this geometry is the portion of the window with shadows excluded).

void render_with_damage(wf::texture_t src_tex, wlr_box src_box,

const wf::region_t& damage, const wf::framebuffer_t& target_fb) override

{

// TODO

}

render_with_damage() is where the real magic happens. We get src_tex and src_box, which are the view texture and the view geometry so far (from previous transformers, if any). damage is the region which we need to repaint, and target_fb is the framebuffer to draw to (it can be either a workspace stream or an auxiliary buffer which will be passed on to the next view transformer, if any).

rounded_corners_transformer_t(wayfire_view view)

{

this->view = view;

}

private:

wayfire_view view;

Finally a constructor where we get the view we’re operating on.

A rounded corners shader

Wayfire utilizes OpenGL ES for rendering, so for the actual rendering we will be using a vertex and a fragment shader.

The vertex shader is pretty straightforward:

#version 100

attribute mediump vec2 position;

varying mediump vec2 fposition;

uniform mat4 matrix;

void main() {

gl_Position = matrix * vec4(position, 0.0, 1.0);

fposition = position;

}

We have our input position and a transformation matrix, and we pass the input position to the fragment shader. Now the fragment shader:

#version 100

@builtin_ext@

varying mediump vec2 fposition;

@builtin@

// Top left corner

uniform mediump vec2 top_left;

// Top left corner with shadows included

uniform mediump vec2 full_top_left;

// Bottom right corner

uniform mediump vec2 bottom_right;

// Bottom right corner with shadows included

uniform mediump vec2 full_bottom_right;

// Rounding radius

const mediump float radius = 20.0;

void main()

{

mediump vec2 corner_dist = min(fposition - top_left, bottom_right - fposition);

if (max(corner_dist.x, corner_dist.y) < radius)

{

if (distance(corner_dist, vec2(radius, radius)) > radius)

{

discard;

}

}

highp vec2 uv = (fposition - full_top_left) / (full_bottom_right - full_top_left);

uv.y = 1.0 - uv.y;

gl_FragColor = get_pixel(uv);

}

top_left and bottom_right uniforms are used to represent the window region that we are actually drawing. full_top_left and full_top_right uniforms represent the full window including shadows. If the current fragment is close enough to a corner, then we can check whether to discard the fragment or not. Otherwise, the color of the fragment is simply the color of the corresponding pixel in the window texture (which includes the shadows, which is why we need full_top_left and full_bottom_right).

There are also two special symbols, @builtin@ and @builtin_ext@. The reason for them is that we are actually writing a shader template. Wayfire’s core will use it to create multiple GL programs for different texture types (some are RGBA, some are RGBX, some are entirely different). The @builtin@ symbols are expanded with the necessary definitions for different texture types and we get a get_pixel(vec2) function that we can use to access the texture.

Next, we need to compile our shaders in the constructor. Wayfire provides a convenient abstraction over OpenGL programs:

// sources from above

const std::string vertex_source = R"(...)";

const std::string frag_source = R"(...)";

// member variable

OpenGL::program_t program;

// in constructor

OpenGL::render_begin();

program.compile(vertex_source, frag_source);

OpenGL::render_end();

We also use render_begin()/end() to ensure we are running in the correct GL context.

render_with_damage() implementation

void render_with_damage(wf::texture_t src_tex, wlr_box src_box,

const wf::region_t& damage, const wf::framebuffer_t& target_fb) override

{

OpenGL::render_begin(target_fb);

program.use(src_tex.type);

program.set_active_texture(src_tex);

upload_data(src_box);

program.uniformMatrix4f("matrix", target_fb.get_orthographic_projection());

GL_CALL(glEnable(GL_BLEND));

GL_CALL(glBlendFunc(GL_ONE, GL_ONE_MINUS_SRC_ALPHA));

for (const auto& box : damage)

{

target_fb.logic_scissor(wlr_box_from_pixman_box(box));

GL_CALL(glDrawArrays(GL_TRIANGLE_FAN, 0, 4));

}

GL_CALL(glDisable(GL_BLEND));

program.deactivate();

OpenGL::render_end();

}

There are quite a few things here. We have our familiar render_begin/render_end() block, this time with a specified target framebuffer where the drawing will take place. We set up our program with the correct texture, upload vertex data and uniforms, and finally, iterate over each rectangle in the damage (the region we need to redraw) and redraw it. We are using scissoring to redraw only the damaged region. The logic_scissor() helper function takes the damaged region in the logical coordinates and transform it to the actual framebuffer coordinates. In the end, we just need to reset all GL state we have used.

std::vector<GLfloat> vertex_data;

void upload_data(wlr_box src_box)

{

auto geometry = view->get_wm_geometry();

float x = geometry.x, y = geometry.y,

w = geometry.width, h = geometry.height;

vertex_data = {

x, y + h,

x + w, y + h,

x + w, y,

x, y,

};

program.attrib_pointer("position", 2, 0, vertex_data.data(), GL_FLOAT);

program.uniform2f("top_left", x, y);

program.uniform2f("bottom_right", x + w, y + h);

program.uniform2f("full_top_left", src_box.x, src_box.y);

program.uniform2f("full_bottom_right",

src_box.x + src_box.width, src_box.y + src_box.height);

}

Here, we are uploading the vertex data and setting the corner uniforms. We use the wrapper functions from Wayfire’s core which will set the uniform for the correct program (depending on the active texture type). We will be rendering the view’s wm_geometry region (the one with shadows excluded), and we are using the src_box region as the full region (it is the whole window with shadows). An important point here is that the vertex data must be stored on the heap (in the vector). This is necessary because that vertex data needs to be still available until the glDrawArrays call.

A note regarding coordinate systems

So far, calculations have been done in several coordinate systems. Wayfire uses three different coordinate systems:

-

Logical coordinate system (LCS). LCS is used for the coordinates of views on a given output, it is the coordinate system that damage tracking works in, and is also the coordinate system for

wf::framebuffer_t::geometry. All in all, this is the most widely used coordinate system. -

Framebuffer coordinate system (FCS). FCS represents the physical coordinates of a view after it is drawn onto the framebuffer. Converting from LCS to FCS is non-trivial: first, the view’s geometry is translated to be relative to the framebuffer’s own geometry (both in LCS). Then, scaling and rotation takes place. The

logic_scissor()method from above does this conversion under the hood to set the GL scissor rectangle. -

Texture (UV) coordinates. The coordinates inside a GL texture. Conversion is done manually, here in the fragment shader.

Set up the transformer

Finally, we should create the Wayfire plugin class, listen for new views and attach the transformer to them. This step has a lot of similarities with the previous tutorial so I won’t be explaining it in detail here.

class wayfire_rounded_corners_t : public wf::plugin_interface_t

{

public:

void init() override

{

output->connect_signal("view-mapped", &on_map);

}

wf::signal_connection_t on_map = [=] (wf::signal_data_t *data)

{

auto view = wf::get_signaled_view(data);

// Ignore panels, backgrounds, etc.

if (view->role == wf::VIEW_ROLE_TOPLEVEL)

{

view->add_transformer(

std::make_unique<rounded_corners_transformer_t>(view));

}

};

};

DECLARE_WAYFIRE_PLUGIN(wayfire_rounded_corners_t);

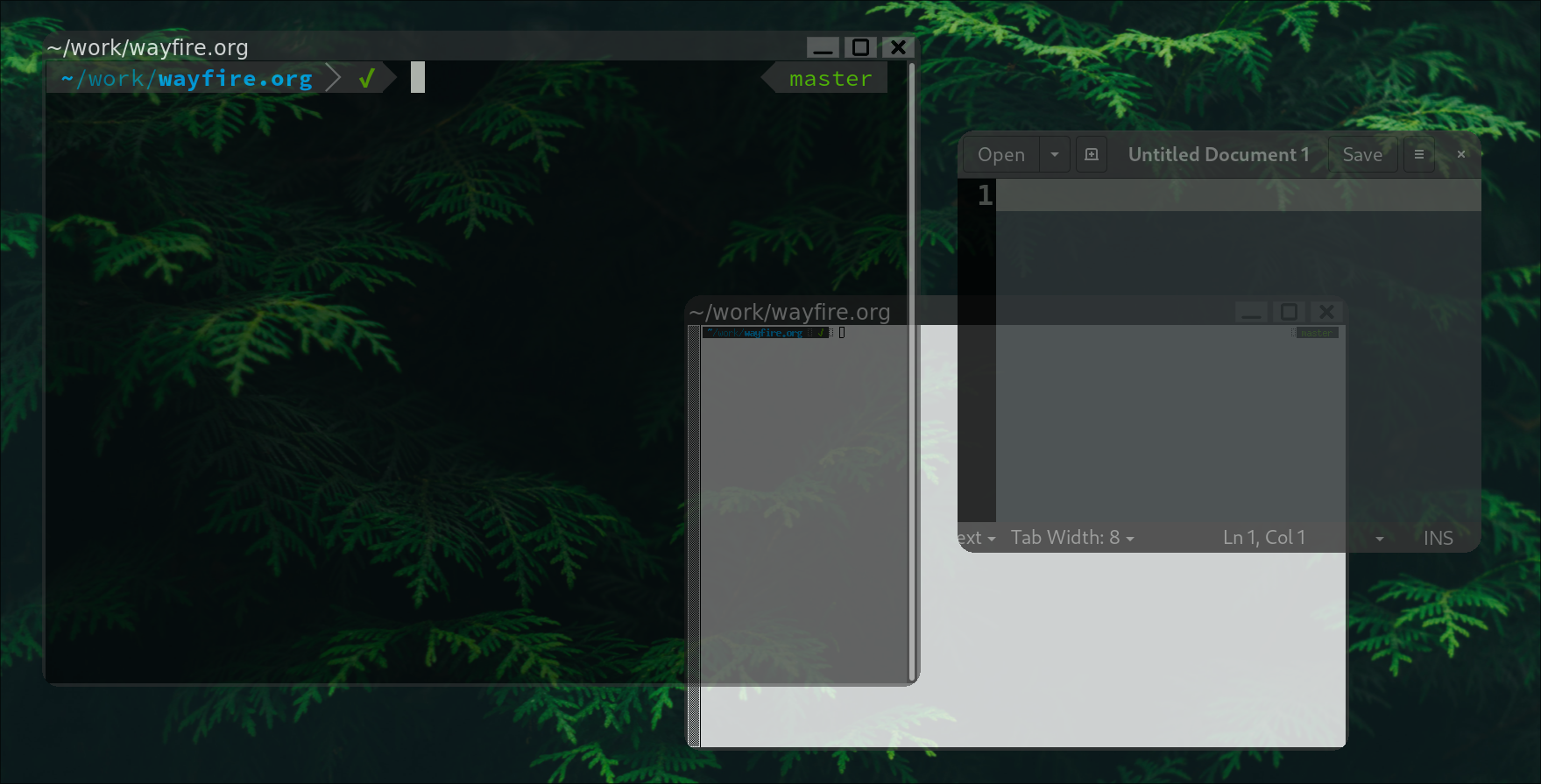

The view-mapped signal is emitted for newly opened views. We filter out views that shouldn’t have rounded corners, and then we add a transformer to the rest. Note that we never remove the transformer in case the plugin is unloaded. This should be done, but is out-of-scope of this tutorial (and does not create problems as long as you don’t dynamically unload the plugin). The end result:

Final words

I hope that now you have a bit more insight on how Wayfire’s rendering works. You can find the whole plugin here. Thank you for reading and stay tuned for further posts on the “Writing Wayfire plugins” series!